Why Most Developers Are Solving the Wrong Problems

You’re not Netflix. Nor are you Amazon, Facebook, or Google. That might sound obvious, yet day after day, developers design systems as if they’re operating at Big Tech scale. We spin up sophisticated microservices for small apps, agonize over multi-region deployments before our first customer even signs up, and add layers of abstraction to handle hypothetical millions of users who may never arrive. In short, we fall into the trap of solving problems we don’t have. And we do it at the expense of the ones we do.

This phenomenon is rampant in our industry. Smart engineers, people who should know better, waste precious time building for a future that isn’t guaranteed. It’s all too easy to confuse technical sophistication with actual progress.

The result?

Projects that are beautifully engineered and fundamentally misguided.

Instead of delivering value to users or businesses, we chase architectures and optimizations suited for companies a thousand times our size. We end up with complexity and “solutions” in search of a problem.

How do capable devs end up here? Two common culprits are at play: the lure of premature scalability — building outlandish infrastructure for day-one projects — and cargo cult engineering — blindly imitating Big Tech’s playbook without understanding the context or whether it’s even necessary in the very first place. These traps are subtle, seductive, and surprisingly easy to justify when you’re in the thick of engineering. As someone who’s wrestled with unnecessary complexity, I want to unpack why these instincts lead us astray, share lessons from the trenches, and offer a few pointers for focusing on what actually matters. The goal isn’t to shame, but to help us all recognize when we’re working for our ego or resume, rather than for our users.

The Trap of Premature Scalability

Every developer knows the adage about premature optimization being the root of all evil. Yet in the era of cloud computing and seemingly infinite scaling, we’ve invented a new strain of that old disease: premature scalability. This is what happens when we pour time and effort into architectures that anticipate success on a massive scale without first validating that our product or feature deserves to scale at all. It’s like building a thousand-room mansion for a family of two, on the assumption that one day you’ll host a city’s worth of guests.

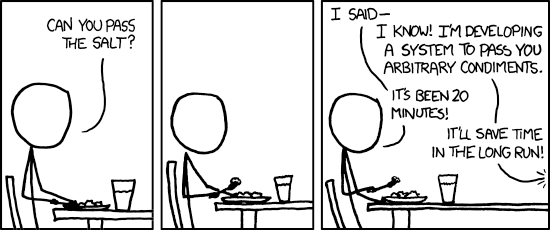

In fact, this tendency is so common it’s a running joke in our industry. A popular comic strip illustrates this perfectly. At a dinner table, someone asks “Can you pass the salt?” and the engineer replies, “Hold on, I’m developing a system to pass arbitrary condiments… it’ll save time in the long run!”. We laugh because it’s true. We’ve all been that engineer at some point, over-complicating a basic request in the name of cleverness or future-proofing.

I’ve witnessed this first-hand. In one early-stage startup I worked with, the team was obsessed with being “enterprise-ready” from day one. They set up Kubernetes from the start, spread their services across multiple environments, and juggled three databases “just in case” they needed to scale. Their setup was far more complex than what their actual traffic demanded. While they were busy building for a hypothetical scale, real customers were still waiting for core features to work reliably. Resources went into orchestration and abstractions instead of solving user pain. By the time their runway got tight, they had an impressive system but very little traction to show for it. A quiet reminder that technical ambition means little without product clarity.

This isn’t an isolated story. Studies have found that nearly 39% of failed startups squander significant resources by over-engineering before finding market fit. Y Combinator’s own Startup School data indicates engineers waste roughly 31% of their runway on things like premature scalability, handling edge cases that never happen, or building proprietary tech no one asked for. The pattern is clear. Solving hypothetical problems too early can be lethal. Every hour spent preparing for a theoretical deluge of traffic is an hour not spent talking to users or refining the product so that a deluge might actually come.

Why do we do this? Part of the allure is emotional. Designing a system that could “scale to millions” feels like a badge of honor. It’s cool, it’s challenging, and it makes us feel like brilliant engineers. There’s also fear at play: “What if our little app does become the next Facebook overnight? We better be ready!” But this fear is usually unfounded. True hypergrowth is rare, and even when it happens, being under-prepared for massive success is a “good problem” to have, one that can be solved when it actually arrives, with the benefit of real data and real revenue. Far more common is the scenario where over-preparation slows your journey to any success at all. In a Hacker News thread, a commenter put it this way: “with great product-market fit, everything can be under-engineered; with poor fit, everything is over-engineered”. In other words, if people desperately want what you’re building, you can get away with a simple, scrappy solution. But if you don’t yet know what people want, no amount of architectural astronautics will save you.

Keep in mind that scalability is not a virtue in isolation. It’s relevant only once you have something worth scaling. LinkedIn’s founders famously said, “If you’re not embarrassed by v1.0 of your product, you launched too late.” Shipping a bare-bones, un-scalable first version that people love is infinitely more valuable than a perfectly engineered system that nobody needs. You can always rework and expand a simple system when the time comes. In fact, that’s how most tech giants started. Facebook began as a single PHP app on one server. Airbnb started as a scrappy Ruby on Rails monolith. These companies didn’t solve global-scale technical challenges on day one. They solved a user problem and gained traction. The scaling challenges came later, and by then, they had the resources (and imperative) to tackle them.

The lesson? Build for the scale you have or are reasonably about to get, not the scale you fantasize about. Solve the problems in front of you. If you’re lucky enough to hit true scalability pain, you’ll be in a far better position to address it after you’ve built something people actually want. Until then, premature scalability is just procrastination wearing an architect’s hat.

Imitating Giants, Missing Context

Premature scalability’s twin sibling is cargo cult engineering. The term “cargo cult” comes from an anecdote of South Pacific islanders who, after World War II, built fake runways and wooden airplanes hoping to summon the wealth (“cargo”) that allied forces brought. In software, it describes teams slavishly copying the outward techniques of tech giants. Microservices here, an event-driven pipeline there, a dash of Kubernetes and Cassandra without grasping why those choices make sense for the giants, and why they often don’t for everyone else.

We’ve all seen it. A two-person startup wires in Kafka, shards their app into ten microservices, and swaps PostgreSQL for something that needs a PhD to run, because that’s what the big guys do. It’s tempting. You read blog posts from Stripe or Airbnb, watch a few conference talks, and suddenly their stack feels like the standard you’re supposed to reach. You start engineering like you’re running a billion-dollar infrastructure when you haven’t even hit product-market fit.

The problem is, those tools were built for scale and pain you probably don’t have. Kafka makes sense if you’re processing millions of events a second. Cassandra exists because Amazon needed to make sure “Add to Cart” never fails. Microservices? They’re a way for giant teams to stop stepping on each other. For most of us, they’re overkill.

I’ve met friends who lost months chasing that kind of architecture. Endless boilerplate, flaky CI, dev environments breaking for no good reason, just to power a system that could’ve been a Rails monolith and a cron job. The worst part? They thought they were doing it right because it looked like success from the outside.

This isn’t about avoiding complexity forever. It’s about knowing when to lean into it. If you’re drowning in users, if your database is creaking under pressure, fine, upgrade. But if you’re building something new? You don’t need to solve Netflix’s problems. You need to solve your own. Clean, boring, reliable tools will take you a lot further than cleverness ever will.

Your client doesn’t care how elegant your system is on the inside.

Solve Real Problems, Not Imaginary Ones

All this talk of what not to do begs the question. How do we refocus on the right problems? It starts with a mindset shift. Remember that at the end of the day, code and architecture are just means to an end. The end is delivering value, solving a real pain point for your users or business. Anything that doesn’t contribute to that is likely a vanity project. Your client doesn’t care how elegant your system is on the inside. They care that you help them solve their problem. Every minute you invest in not giving them value is time wasted. It’s a hard truth for those of us who take pride in our craft, but it underscores a crucial point: elegant engineering is not the goal; useful outcomes are.

So, how can you tell if you’re working on a meaningful problem or just polishing your ego? A few litmus tests and habits can help keep you honest:

- Ask “What if we don’t do this?” If the honest answer is “nothing bad happens” or “the user wouldn’t even notice,” that’s a strong sign you’re dealing with a vanity problem. Real problems have tangible consequences if left unsolved. If a proposed feature or architectural change won’t clearly improve user experience, performance, reliability, or developer productivity in the near term, question why you’re doing it now.

- Channel your inner product manager. Before diving into a technical rabbit hole, articulate the user benefit or business value it will create. Are you paginating that API response because users are actually asking for it, or just because you saw it in a “best practices” checklist? Tie every significant engineering effort to a clear “so what?” in plain language. If you can’t, that’s a red flag.

- Embrace YAGNI (“You Aren’t Gonna Need It”). This classic principle is a compass for avoiding over-engineering. Build for the requirements you know you have right now, not for distant possibilities. Implementing a complicated layer “just in case we need it later” is usually a recipe for waste. Later, you’ll either have actual evidence that you need it or you’ll be very glad you didn’t sink time into it.

- Prefer simple and boring to clever and cool. Fancy architectures and cutting-edge tools are fun, but ask yourself: is there a simpler solution that gets the job done? Often, “boring” choices like a straightforward CRUD app, a single reliable database, or a well-understood framework will deliver value faster and with less risk. You can always spice things up once the basics are solid and the real needs emerge. Don’t build a Ferrari when a bicycle will do.

- Keep an eye on actual usage and pain points. Let data and feedback drive your investments. If you’re worried about scaling, set up some basic monitoring and alerts, not a whole distributed system. If you’re unsure about a design, build a quick prototype or even a manual workaround to test the need. Measure what matters (load, response times, user behavior) and let those numbers tell you when a problem is real enough to warrant a big engineering effort.

Cultivating these habits provides a sort of reality check in your engineering practice. It steers you away from what Fred Brooks called “accidental complexity” — the complexity we needlessly create — and keeps you focused on the essential complexity of actually delivering what users need. It also makes work more rewarding in the long run: you’ll spend more time solving problems that make a difference, and less time maintaining overbuilt contraptions that impress no one but your own inner architect.

Finally, remember that saying “no” (or “not yet”) to certain ideas is not anti-engineering, it’s good engineering. It takes discipline and experience to hold back the impulse to add “one more layer” or chase a shiny new tool. But that discipline is exactly what separates senior engineers from novices. Experienced developers have the scar tissue to know that every abstraction and every server you add comes at a cost. They’ve felt the pain of debugging an overly complex system at 2 AM, and they’ve learned to be judicious about what problems are worth that pain.

In the end, nobody gives out awards for the most over-engineered system. Users reward solutions that work. Ones that solve their problems reliably and intuitively (often with less complexity, not more). Businesses reward products that reach the market in time and adapt quickly to change, not ones stuck in perpetual “engineering mode.” The most impressive engineers aren’t the ones building imitation Google infrastructure in a vacuum, they’re the ones delivering impact with balanced, context-aware design. So the next time you catch yourself spinning up a needless component or agonizing over a problem only Big Tech would have, take a step back. You’re not Big Tech, and that’s your superpower. It means you can choose simple, pragmatic solutions without apology. It means you can focus on your users and your unique challenges.

Those are the problems worth solving.

That’s where the real engineering happens.

Enjoyed this piece?

If this piece was helpful or resonated with you, you can support my work by buying me a Coffee!

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion