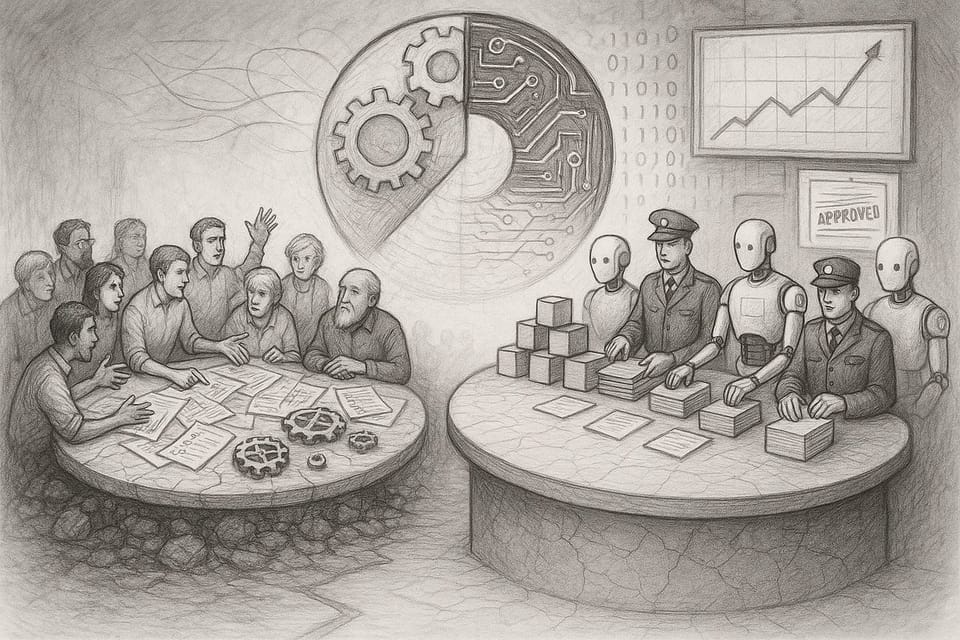

How our faith in perfect algorithms threatens real self-correction, and why democracy survives by making room for noise.

People trust systems that promise order. I once saw a team spend weeks building a product under a manager who didn’t invite questions. He made all the calls. No debate, just follow the plan. On paper, things looked good until the day a serious bug surfaced, one that nobody had wanted to mention. We lost days undoing the damage. The cost wasn’t just time. It was that queasy feeling you get when you realize silence is built in.

Over time, I’ve run into this theme in different setups and at different scales.

Reading Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus Chapter 5 on democracy and dictatorship as rival information networks put language to something I’ve felt for years. His framework helped me see how this dynamic plays out from office politics to world history — and now, in the age of algorithms, it feels more urgent than ever.

Memories like that nag at me whenever I watch how much faith we put in algorithms, policies, or “best practices.” We like things that seem infallible. Something or someone to take the uncertainty away. But in every system, the thing you ignore has a way of circling back.

Democracy is supposed to let in noise. Totalitarian systems promise quiet. Today, technology keeps tipping us toward the latter. There’s a real risk we’re trading our messy, hard-won feedback loops for a new kind of automated certainty and not pausing to ask what that means.

Democracy: The Self-Correcting Conversation

Yuval Noah Harari describes democracy as a network. Messy, distributed, and full of overlapping voices and feedback loops. It’s built to make noise. Elections, free press, independent courts, peer review—none of these are just rituals. They exist to create doubt and correction. Mistakes happen, but they get argued over and sometimes overturned. At its best, democracy is a country arguing with itself, willing to change direction when the facts demand it.

History backs this up. In the United States, outrage over the Vietnam War forced a hard shift in policy. The country was divided, but the public argument dragged mistakes into the open. In other places, similar wars stayed quiet. The problems were hidden, and lessons took longer to surface. Discomfort in a democracy isn’t a flaw. Sometimes, it’s the only way to learn.

I’ve seen hints of this in my own experience. In some places, stability and order are the main priorities. Debate rarely makes the headlines, and most people try not to rock the boat. But now and then, something gives. More people show up to vote. Unexpected outcomes shake things loose. The process is usually messy, sometimes chaotic, but it’s proof that the system isn’t dead. Debate, protest, criticism—these are signs that a society can still heal itself, not symptoms of decline. When I hear complaints that democratic argument is “just noise,” I hear something closer to a heartbeat.

Harari puts it plainly. Dictatorship pulls power into the center and closes off correction. Democracy spreads power out, leaving room for disagreement. In a real democracy, no one election or leader is above the rules. There are always other channels—media, courts, academic voices—to push back when things go wrong. If a government, once elected, crushes dissent, it’s already broken the feedback loop that keeps it honest. Elections are just society’s way of admitting it might have been wrong and giving itself a second chance.

Democracy is built on humility. No one gets the final word. A free press can topple a dishonest minister. A judge can overturn an unjust law. Scientists can force a policy rethink with new evidence. These aren’t failures. They’re signs the system is working. Institutions checking each other, redundancy, debate—these things slow down decision-making, but they keep the whole thing from breaking under pressure.

There’s a spiritual side to this for me. I grew up hearing stories about prophets challenging kings, apostles arguing doctrine, and warnings against trusting leaders blindly. Even the most respected are fallible. That’s the core of real democracy, science, and faith communities: the willingness to admit mistakes and keep looking for truth. As Augustine said, “To err is human; to persist in error is diabolical.” A civic culture that understands this will always leave the door open for debate and correction. If we get it wrong, we have to try to set it right.

The Allure of Perfect Order

But there’s a pull in the other direction. If democracy sounds like a crowded town hall, its opposite is a quiet control room. Totalitarianism, or any system that leans that way, can be seductive for those weary of chaos. “At least the trains run on time,” some say, longing for someone to take charge and silence the bickering. In moments of crisis, I’ve felt that urge myself. Sometimes I wish someone else would make the call, just to trade arguments for order.

Authoritarian systems sell themselves as smooth and efficient. Information funnels to the center. Loyalty is demanded, not requested. Dissent becomes not just inconvenient, but forbidden. When the system insists it’s never wrong, questioning it feels like a crime. For a while, it can look powerful. Decisions come quickly. Policies roll out without debate. Big projects, industrial drives, and ambitious infrastructure get done, at least on paper. In wartime, democracies sometimes envy this kind of speed.

History is clear about the costs. In any system where leaders cannot be questioned, officials report imaginary successes to meet impossible quotas. On paper, the results may look miraculous; in reality, disasters unfold because no one dares acknowledge what’s going wrong. When authority goes unchecked, mistakes go unchallenged and the bill only grows.

Top-down plans often produce waste and hidden harm that nobody feels safe to address. Again and again, we see what happens when early warnings are suppressed and truth-tellers are punished: problems stay buried until disaster forces them into the open. Systems obsessed with perfect order often create silence and fear. They hold for a while, then crack all at once.

This dynamic isn’t limited to politics. I once worked for a boss who prized vision and demanded loyalty. For a while, his “yes men” made things run smoothly. But when the market changed, the lack of honest feedback nearly tanked the company. Only a last-minute intervention brought conversation back, and with it, a shot at survival. A system that shuts out dissent might work for a season. Then it falls apart.

The draw of perfect order is real. It’s easier to keep the peace by ignoring problems, hiding mistakes, and insisting on unity. But that peace is brittle. Democracies move slower and quarrel more, but their arguments act as shock absorbers. The system bends instead of breaking. It’s better to have the debate now, in the open, than to pay the price for silence later.

The Rise of the Algorithmic Governor

Now the old tug-of-war between democratic messiness and authoritarian control is being reshaped by technology. I build software for a living. I pay attention to how these systems play out in the world. Technologies that once helped democracy scale, like printing presses, telegraphs, and broadcast media, have also made it easier to centralize power. Today, AI and big data let a single authority reach further than any emperor could have imagined.

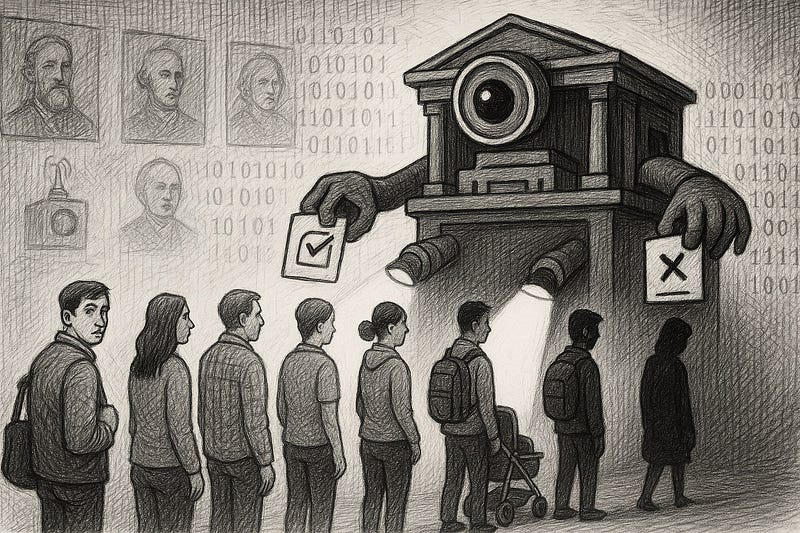

We’re living with the results. In some countries, AI-driven cameras track people in public spaces, making protest risky. During recent mass demonstrations, people tried to dodge surveillance with masks and lasers, knowing algorithms could pick individuals out of a crowd. Other governments use similar tools to monitor dissent. The effect is suffocating. Technology becomes a tool for silencing, not for listening.

But it isn’t just autocracies. In democracies, we give more and more decisions to algorithms, chasing speed and efficiency. Social media platforms pick which news and opinions go viral. Recommendation engines quietly decide what millions of people see or miss. The internet was supposed to democratize speech. Instead, most attention now flows to a handful of giant hubs. Each has its own logic, and nobody outside gets to see how it works. The line between censorship and algorithmic filtering has blurred.

Even public services are tempted. Around the world, city governments and ministries have started exploring AI tools to allocate resources, automate approvals, or even rate teachers. On paper, it sounds neutral. No bias, just data. But algorithms carry the flaws and blind spots of their makers, only faster and at a bigger scale. When Detroit police arrested an innocent man because facial recognition pointed to him, nobody wanted to question the software. In New York, lawyers trusted ChatGPT to write a brief. The AI made up fake cases, and nobody caught it until too late. This isn’t new. We build a tool, call it neutral, and then forget it’s just another imperfect system.

There’s a deeper risk. The more we let machines decide, the more we trust their output by default. The process is hidden behind code. We rarely see how these decisions happen. It’s easy to believe a computer is objective, even when it isn’t.

Harari noticed a shift. In the past, even absolute rulers needed human interpreters. Now AI can write the rules and interpret them too, with no human in the loop. If we start trusting these systems just because they’re fast and complex, we’re building digital authorities that answer to no one.

I don’t think algorithms are out to get us. The real danger is simple. We invent something, declare it infallible, and stop asking questions. When that happens, mistakes pile up quietly. An AI won’t sound an alarm when it’s wrong. It just keeps producing answers. It’s still up to us, as flawed and biased as we are, to ask, “Are we sure?” and step in when the system drifts.

Keeping Humans in the Loop: A New Covenant of Fallibility

So where does this leave us? I’m not saying we need to smash our computers or hold debates by candlelight. Technology, including AI, can serve democracy and make life better, but only if we keep our eyes open and our hands on the controls. The point isn’t to fear our tools or treat them as sacred. We just need to stay humble.

That means admitting we might be wrong, and putting safeguards in place to catch ourselves. It means building systems so that, when mistakes happen, someone can spot them and fix things. Harari says it simply. Let’s drop the fantasy of perfection, and do the steady work of building checks, audits, and corrections into every important system. Sometimes that feels slow or just plain annoying. But a little friction keeps things honest.

For governments, this means algorithms should never be the last word. After that wrongful facial recognition arrest in Detroit, new rules banned using an algorithm as the only reason to arrest someone. It’s common sense. Trust the tool, but double-check the results. More broadly, we need independent watchdogs, active journalists, and outside experts who review these systems. The more power an algorithm has, the less right it has to work in the dark.

The same principle holds for organizations. Debate and dissent aren’t problems to be fixed. They’re features. In engineering, we do code reviews and test runs for a reason. Civic life could use more of that. Regular sanity checks, open forums, and a willingness to invite outside criticism all help. If the people in charge never get challenged, the whole system drifts.

At home, it’s the same spirit, just closer to the ground. My wife and I let our kids challenge us — politely, if they can make their case. We admit mistakes in front of them. Dinner is noisy and sometimes frustrating, but I hope it teaches them to ask hard questions and not to swallow answers just because someone in charge said so. They’ll need that habit in a world run by algorithms and persuasive apps.

None of this means we’re rooting for chaos. The goal is real order, not the brittle kind built on silence. We want institutions that can change when the evidence changes. We want tools that stay tools, not become masters. A map isn’t the land. A model isn’t reality. If we start worshipping the plan instead of facing what’s real, we’re asking for trouble.

I think about this a lot as a Christian. There are old warnings about false idols. Today, our idols might be databases or machine learning models, promising certainty in a world that’s always uncertain. Sometimes we want to hand over control, just to avoid doubt. But living with uncertainty is how you grow wise. Blind faith, whether in an algorithm, a leader, or a doctrine, always ends badly.

Let’s use our tools. Let’s never give up our judgment. Stay curious. Keep asking the hard questions. Algorithms can’t lose sleep over a bad decision. That’s our job, and it always will be.

Conclusion

Most days, I’d pick an honest skeptic over a system that claims it’s always right. I trust people who argue, even when they drive me crazy, more than any program that never admits it’s lost. Real democracy is messy. It wears you out. Sometimes, I wish someone would just give the answer and let everyone move on. But every shortcut I’ve seen, every time a team, a company, or a country chooses silence for the sake of order, it ends badly.

I keep thinking about my kids. Someday, they’ll live in a world crowded with AI and clever machines. I hope they don’t learn to stay quiet just because the system sounds certain. I hope they feel free to speak up. I hope they ask obvious questions, even if their voices shake. I hope we remember that our doubts, awkward or loud or stubborn, are what keep us human.

Nobody gets the last word on how we live together. Not a law, not a leader, and definitely not an algorithm. We make the rules. We rewrite them together, every time we refuse to settle for easy certainty.

That’s what I want for them. That’s what I want for us.

Viz

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion