Breaking Free from Growth-at-All-Costs Thinking

No one ever bought a product because it ran on Kubernetes. Customers want their pain solved, not your architecture story. Most startups don’t need microservices. They need to survive.

This is a contrarian view in a software world hooked on hypergrowth and “planet-scale” ambition. Somewhere along the way, we stopped asking the only question that matters: Should software scale at all? Or, put differently, when does scaling become a liability, not an achievement?

Today, most teams are pressured to “think big” before they even find users. We celebrate billion-row databases and distributed everything, then act surprised when the product never finds its footing. This isn’t just a technical problem; it’s cultural, economic, and psychological. I’ve seen it firsthand, leading teams asked to scale for imaginary millions instead of real needs.

Why did “scaling up” become the one true measure of progress? What are the hidden costs when we build systems and teams for a future that never comes?

How does this scale? What if we have 5 million users by next quarter, and half of them are in South East Asia?

Scale the Badge

In tech, “scale” is often shorthand for success. Startups brag about serving millions. Founders talk about going global before they have a hundred users. Everyone loves a chart that shoots up and to the right. We borrowed this mindset from old industries like factories and logistics, where making more meant saving money.

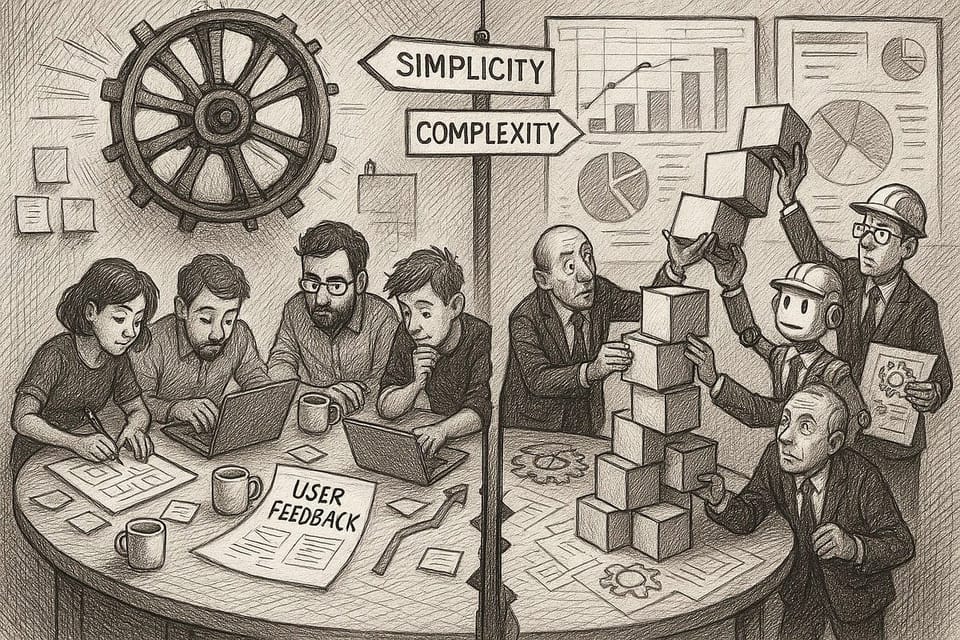

But software doesn’t work that way. When the codebase or the team gets bigger, everything slows down. Five developers on a small project move fast and know what’s going on. Fifty developers on a big system start to get lost. Every extra layer means more meetings, more mistakes, and more stuff to keep in your head.

Still, we treat scale like a trophy. Building with microservices, spinning up more infrastructure, adding the latest tools all look impressive on paper. People love to say the app is “enterprise-ready,” even when it just serves a few customers. The web used to be a place for simple sites. Now most teams default to full-stack everything, even if the job doesn’t need it.

The truth is, users don’t care about your stack. They want something that works. Every time we add new layers just to feel “big,” the product gets harder to build, harder to debug, and easier to break. We end up with complexity for its own sake. Teams burn out. Bugs pile up. And nobody’s really sure if it’s worth it.

Most of the time, the real problem isn’t that we don’t scale enough. It’s that we confuse looking important with being effective, and pay for it in wasted effort and fragile systems.

How do we convince the board we’re ready for hypergrowth, even though we’re still in private beta?

Growth at All Costs

The pressure to scale isn’t just cultural. The economics of tech reward the illusion of speed and size. Investors want graphs that shoot upward. Founders feel the need to impress with “hypergrowth” even before their product works. Teams build for a future with millions of users, not for the customers they actually have.

Most of this comes from fear. If you don’t “build for scale,” the thinking goes, you’ll get caught unprepared if lightning strikes. Stories like Friendster’s collapse haunt every founder. But for every company that dies from scaling too late, dozens die from scaling too early.

They waste time, cash, and sanity solving problems they don’t have.

Engineers are guilty too. Most want to do things “the right way,” which usually means copying whatever the big tech companies do. Microservices, distributed databases, Kubernetes—these are solutions for real scale, but most startups have a fraction of the users. It doesn’t matter. Building with these tools looks sophisticated, and everyone wants a resume that sounds impressive.

A monolith feels boring. Shipping features and talking to users can wait.

This is how you end up with teams that have more services than customers. A founder raises a seed round, hires engineers, and by month three the app is split into seven microservices and three databases. There are no users yet, but plenty of status dashboards. By the time anyone notices, the runway is burned and the core product is half-baked.

The worst part? The industry celebrates this behavior. Startups get featured for technical deep dives, not customer stories. The glory is in big architectures, not simple wins. Even the cloud providers cash in by selling “enterprise” tooling to teams who could run fine on a single server.

Complexity signals ambition, even when it leads nowhere.

Scaling too early is a slow bleed. Every new abstraction becomes a potential bug. Every extra service adds another thing to maintain. Teams end up stuck in meetings and release planning, with less time to ship. The real work gets crowded out by architectural theater.

This isn’t about resisting growth when it’s real. It’s about refusing to build for a fantasy. Your first job is to find out if anyone cares. If your system can handle ten times your current load, you’re already ahead of the curve.

Focus on the product. Leave the heroics for later, if you need them.

But what if marketing runs a campaign and suddenly everyone on that region logs in at midnight?

The Hidden Costs of (Over)Scaling

Scaling always looks good on paper. Add more users, more code, more servers, more developers.

In reality, every step makes things messier, not just bigger.

Take complexity. Every abstraction, every tool someone adds, makes the whole system harder to follow. You end up with distributed caches, message queues, layers of APIs — most of them pitched as “best practice.”

Used wisely, fine.

Pile them on too early, though, and you wind up with a codebase nobody actually understands. Something breaks and now you’re stuck tracing a bug across five different teams, two databases, and a bunch of tools you barely remember setting up.

Coordination gets worse, too. The more people involved, the more you find yourself in meetings and status calls instead of building. Suddenly, fixing a small bug means negotiating with teams in three time zones. “Team autonomy” sounds great until you’re waiting days for someone else to merge a pull request.

Quality drops. Teams drift apart, code standards split, one group changes a user ID and another rewrites the API. Libraries go out of sync. Now you’re patching bugs that only exist because the left hand can’t see what the right hand is doing.

But what stings most is losing ownership. Small teams move fast and care deeply. Big systems turn everyone into a specialist. You fix your piece and pass the rest along. Creativity dries up, and so does any sense that the product is really yours.

Scaling isn’t just a technical cost. You pay for it in time, money, energy, and sometimes in morale. Most of that pain? Totally avoidable if you don’t overbuild.

Over-Scaling vs Under-Scaling: Both Have Risks

Scaling too soon is expensive, but not scaling when it matters is deadly. Friendster was the original cautionary tale. Their tech failed just as millions showed up. The site became slow and unreliable, and people left.

MySpace took their place, not because it was better, but because it worked.

On the other hand, most teams never hit this problem. They build as if they’re the next Facebook, then struggle to find even a thousand users. All that upfront work, the microservices, the multi-region cloud setup, the fancy monitoring, turns into wasted money and time. Meanwhile, the team that started with a simple monolith ships features, listens to customers, and lives to see another day.

Context is everything. Scale only matters when you have real signals that your current system can’t keep up. Slow load times, users complaining, hard resource limits.

Until then, big-architecture dreams are just a distraction.

Even tech giants are changing course. Some are pulling microservices back into larger units to regain simplicity and speed. The lesson is clear: don’t overbuild just to look sophisticated, and don’t wait until users are leaving before you adapt.

Know where you are, know what you need, and tune for real pain, not for an imaginary scale.

When Scale Helps and When It Hurts

There are times when scaling saves you. Friendster died because it didn’t. Twitter, in the early days, nearly went down for good thanks to the infamous “Fail Whale.” Their team rebuilt the system in a hurry, splitting out traffic, caching, and scaling up infrastructure. Users didn’t care about the details. They just wanted a service that worked. If your product is growing fast, scaling is not optional.

If you stall, users leave.

But most stories aren’t about growing too fast, they’re about overbuilding too soon. Segment, the analytics startup, tried to copy big-company practices before they needed them. Hundreds of microservices, each owned by a small team, seemed smart at first. Reality hit hard: constant outages, slow development, and bugs everywhere. They spent months reversing course, moving features back into a single monolith just to survive.

On the flip side, too many teams “scale for scale’s sake.” They take what works for a unicorn and force it onto a side project. Simple content sites become full-stack, client-rendered monsters. Everyone wants to use the hottest stack. The end result is usually the same: slow sites, tangled code, and missed deadlines.

There are rare cases where early bets on scale pay off. WhatsApp, before Facebook bought them, built their system for millions, even when they only had thousands. It paid off only because their product actually took off. For every WhatsApp, there are hundreds who never needed the fancy architecture.

Most of the time, premature scaling hurts more than it helps. The art is knowing which story you’re living. Are you drowning in real user demand, or just playing defense against a problem you don’t have?

Questions to Ask Before You Scale

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule for scaling. Every team wants a checklist, but scaling only works if you’re honest about your real needs. Here’s a set of questions to keep you grounded before you add complexity:

- What’s actually breaking right now?

Is your system slow, down, or unreliable? Are users leaving because of it? If not, scaling is a distraction. - Do you have product-market fit?

If you’re still searching for users, don’t bother scaling. Stay scrappy and ship fast. - Where’s the real bottleneck?

Is it code, database, infrastructure, or people? Sometimes a small tweak solves the problem. Don’t overhaul the whole system for a single slow query. - Are you burning money for imaginary scale?

If your cloud bill is huge but your traffic is tiny, something’s wrong. Spend on real pain, not on status symbols. - Can your team handle the complexity?

Don’t add systems you can’t manage. Scaling only works if your team understands what’s going on. - Does scaling now actually improve user experience?

Will your changes make things faster or more reliable for users? If not, pause. - Is there a simpler way?

Could you add a cache, split a table, or modularize your monolith instead of rebuilding everything? Simpler is usually better. - Are you ignoring real growth?

If user numbers are doubling every week and support tickets are piling up, don’t wait. Get ahead of the pain. - Will this lock you in?

Be careful with choices that are hard to undo. Start with flexible designs where you can. - Is this about ego, or about solving real problems?

If the main reason to scale is to feel like a “real” tech company, stop.

Use these questions with your team. Scaling should be a response to reality, not a reflex or a resume-builder.

Rethinking Scale as a Goal

Most teams think more is always better. In reality, the best software grows on purpose, not by default. Complexity, size, and clever architectures are easy to brag about, but none of them matter if the product isn’t fast, reliable, and useful.

There’s no prize for the biggest system or the trendiest stack. The real wins come from building what people need, shipping it fast, and keeping things simple for as long as you can. Scaling is just a tool. Use it when you actually need it, and never to impress anyone.

The next time when someone asks, “How will this scale?” ask them what you might lose by scaling too soon. Sometimes, the boldest move is staying small until you have no other choice.

What would change if we only scaled in service of real growth, not for status? How many products and teams would be better off if they just focused on what works right now?

Viz

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion