The Peril of Infallible Systems

People have driven into lakes because their Waze said so. There was even a news story I once read: rescue divers had to pull a car from dark water after its driver followed turn-by-turn directions straight off a boat ramp in Massachusetts. It’s an absurd headline, but a useful parable. Every day, we trust systems that claim to know better — an app, a policy, a sacred text. We curse “computer errors” as if a silicon oracle betrayed us. We click “Accept” without reading. Why question the algorithm’s wisdom?

We want something infallible to guide us. But history shows that this longing can lead us into real danger, not just embarrassment or inconvenience.

The Old Dream of Never Being Wrong

Humans have always searched for something certain. In ancient times, people turned to gods, sacred texts, anything that felt unbreakable. Take ancient scriptures. Some started as scattered scrolls, argued over for generations before they became “official.” By the fourth century, the canon was set. Suddenly, those pages seemed untouchable. Even kings and priests deferred to its sacred authority.

But the real power often slipped — not just to the text, but to whoever got to explain it. In Judaism, the scholars debating the meaning of the law often ended up with more authority than the law itself. The same thing happened in Christianity. Once the New Testament was accepted as above question, the institution could use its authority to shut down rival ideas. “Heresy” was whatever didn’t fit the official line.

People do this outside religion, too. Roman emperors called themselves gods. In the last century, you had parties and leaders who painted themselves as flawless — never to be doubted. Stalin’s Russia: question the plan, and you’re a traitor. When the Bolsheviks insisted their way was perfect, they tore down anything that might challenge them.

Doesn’t matter what era you’re in. The pattern repeats: claim perfection, squash any pushback, keep things looking neat. Of course, under the surface, it’s just fear and silence.

Witch Hunts and the Wages of Certainty

History shows that crusades against “error” often cause more harm than the mistakes they aim to stamp out. In early modern Europe and America, witch hunts took on a life of their own. Authorities felt so sure the Devil was at work that they built entire systems to validate that belief. The printing press, celebrated for spreading knowledge, also fueled the hysteria. In 1487, a Dominican inquisitor published the Malleus Maleficarum, a manual for detecting and destroying witches. Thanks to mass printing, paranoia spread quickly. Sensational pamphlets, filled with lurid images, convinced thousands that a vast satanic conspiracy was real.

Armed with these “infallible” truths, officials turned suspicion into policy. Councils and church courts issued handbooks and even fill-in-the-blank forms for accusations. They created the official category of “witch” almost out of nothing — one label and all doubt vanished. Most victims were women. The courts, the treatises, the “tests” — they all agreed witches existed and must die. Tens of thousands lost their lives to a fiction no one was allowed to question.

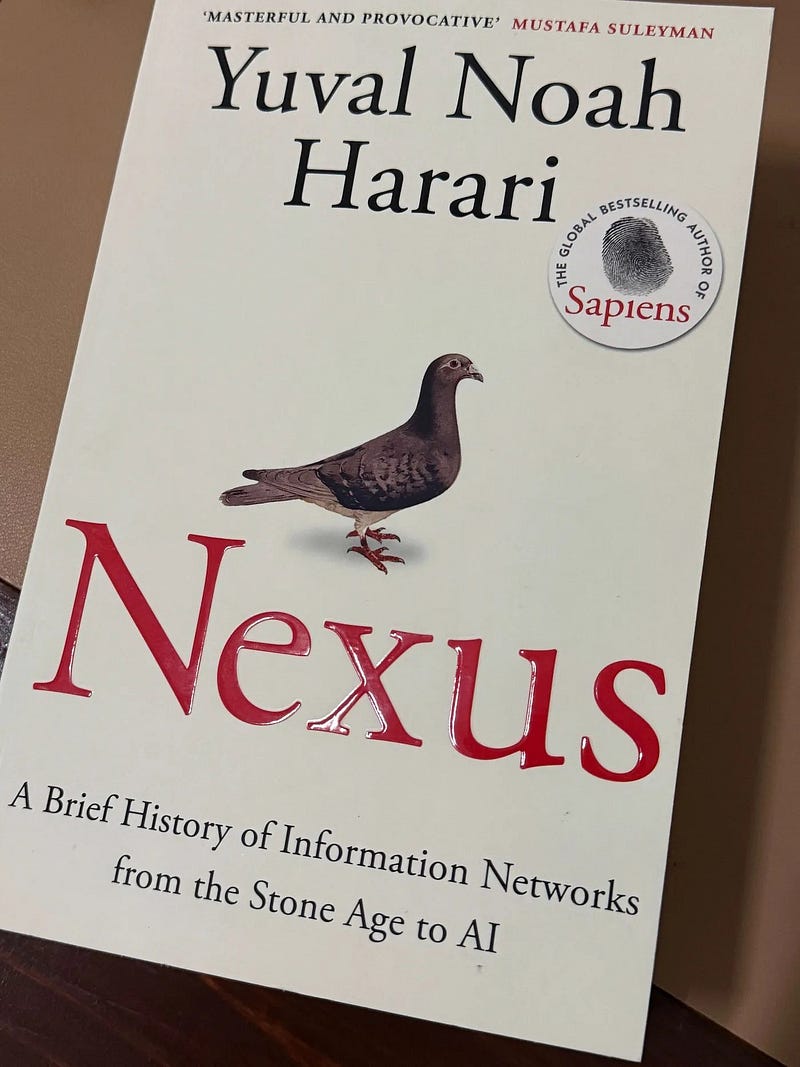

The tragedy fed on itself. Each forced confession became “proof” that witches were everywhere. In one German city, a chancellor wrote of his horror, yet admitted that with so many reports, it was “difficult… to doubt all of it.” Even some accused witches began to believe they were part of a plot. As Harari puts it, the witch hunts were “a catastrophe caused by the spread of toxic information” — a nightmare made worse by more and more of the wrong kind of evidence. No amount of pamphlets or learned arguments could break the spell, because the premise was never up for debate. The belief that the system could not be wrong destroyed real lives.

Yet even here, a new idea was growing: admitting error is a kind of wisdom. By the 17th century, some thinkers started to say that no book, court, or oracle was above question. The Scientific Revolution took root as a culture of fallibilism — a willingness to say, “We might be wrong; let’s check.” Science institutionalized self-correction. Its proudest moments come when new evidence overturns accepted wisdom — when Newton gives way to Einstein or the orbit of Mercury rewrites the map of the cosmos. In science, error is not sin. Experiments exist to find flaws. Journals exist to share them. The very structure rewards those who challenge authority. Prove your professor wrong, and you get a round of applause, not a burning at the stake.

Science’s biggest leap was social: it built mechanisms for correcting itself. Peer review, replication, open debate — messy, but vital. Harari points out that scientific bodies actively seek out their own errors. In contrast, systems like the medieval Church or the Soviet Party avoided self-correction because to admit error would threaten their power. Where order demands pretending to be perfect, truth requires risking disorder by saying, “We were wrong.” History shows that systems that admit fallibility can fix themselves and get better. Systems that pretend to be perfect only pile up mistakes — until something breaks.

The AI Oracle and the Return of the Infallibility Fantasy

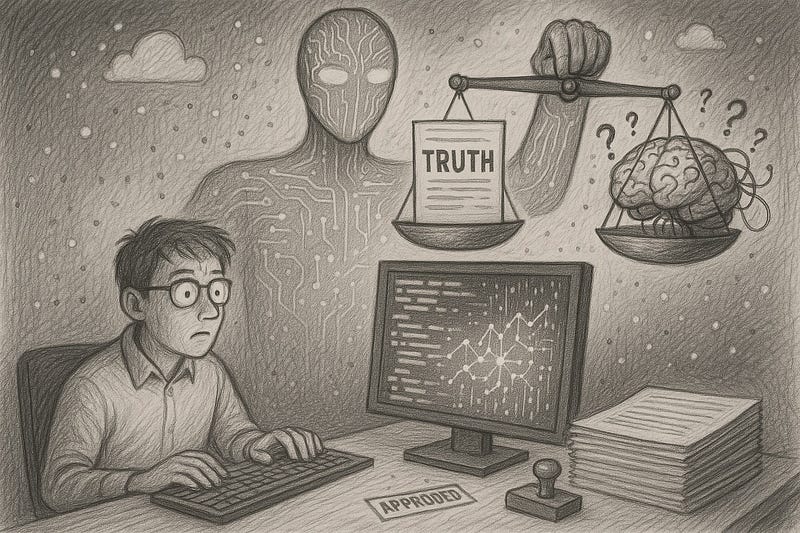

Fast-forward to today. Digital algorithms and artificial intelligences now thread through daily life, doing things that would have looked like magic to the witch-hunters of old. Yet the core human impulse hasn’t shifted much. Our need for certainty, for an all-knowing guide, has simply found new outlets. Many people hope AI will become the perfectly rational, unbiased decision-maker we’ve always wanted — a superhuman mind, free of human mistakes. After all, computers don’t get tired or emotional. An algorithm, we’re told, simply computes the truth. Isn’t that what we need to finally escape human error?

This idea tempts us because it feels like a solution. But it’s dangerously wrong. AI can sift data at impossible speeds, spot patterns we’d miss, and even create art and text that seem uncannily human. Yet the more powerful it gets, the more people treat its output as gospel. We joke about GPS leading us astray, but what happens when a medical AI tells a doctor which tumor is malignant? Or when a policing algorithm labels someone a high risk? Increasingly, these judgments arrive stamped with an aura of objectivity — math, code, no human bias. How could a machine be prejudiced or wrong?

It doesn’t take much for an algorithm to get things wrong. After all, it’s just lines of code written by people and trained on messy, real-world data. If you feed AI examples that are biased, it’ll repeat those patterns — or even exaggerate them. Ask a vague question, and it’ll still give you an answer, sounding completely confident even if it’s way off base. The thing is, these systems have no gut feeling, no common sense, no way to pause and rethink. If the response sounds right enough, they just go with it — even if that means making something up out of thin air.

We’ve seen real-world consequences. In 2020, Detroit police arrested an innocent Black man after a facial recognition system flagged his driver’s license as a match for a crime. Officers trusted the computer’s word — it must be him. It wasn’t. The “system” said he was guilty, and for a moment, that was all that mattered. This was the first known case of a false algorithmic arrest in the U.S., and it didn’t stop there. A 21st-century echo of the witch label: a flawed program defines a person as criminal, and unless someone steps in to question it, the damage is done.

Even in smaller stakes, blind faith in AI trips people up. In New York, a group of lawyers filed a brief packed with case law — except several of the cases didn’t exist. The AI they’d used, ChatGPT, invented them out of thin air. One attorney confessed he “failed to believe that a piece of technology could be making up cases out of whole cloth.” They trusted the machine as if it were an infallible legal expert, and it confidently led them astray. It’s the GPS-in-the-lake, but in a courtroom.

What’s worse, today’s infallibility fantasy often works invisibly. You used to know when you were facing a scripture or a powerful leader. Now, algorithms quietly sort and score us in the background. Search engines, hiring tools, and content moderators — each presents itself as neutral, yet often quietly cements old prejudices or makes mistakes we never notice. We rarely question black-box decisions unless a glaring error appears.

Harari offers a new warning: in the past, infallible texts still needed humans to interpret them. But now, he says, AI “not only can compose new scriptures but is fully capable of curating and interpreting them too. No need for any humans in the loop.” We’re on the verge of self-contained systems that generate their own rules and act on them, without oversight. If we trust these simply because they’re fast and efficient, we risk a nightmare more chilling than any paper bureaucracy — an autonomous, digital authority that’s accountable to no one.

AI isn’t an evil force out to destroy us. The danger is the old one: believing the system is always right. That belief invites us to stop asking questions and hand over our judgment. That’s when errors can snowball — quietly, but with real consequences.

Keeping Humans in the Loop: A New Covenant of Fallibility

So what now? Throw out the rulebooks, pull the plug on AI, or smash every bureaucracy? Not at all. The answer isn’t to swing from worshipping our systems to fearing them. Bureaucracies, for all their flaws, gave us things like birth certificates and clean water — mundane but vital. Religious texts have inspired art, community, and ethics, even if they were sometimes misused. AI, too, promises breakthroughs in medicine and education. Tools keep changing, from clay tablets to supercomputers. What matters is whether we keep our ability to question those tools — and the people behind them.

We can’t give up our judgment, no matter how impressive a system looks. Every tool or institution is a means to an end, not the end itself. A map is not the territory. A model is not reality. When we forget this, the “paper tigers” and false idols can bite.

I’ve written before about how bureaucracy, for all its ordinariness, can become a paper tiger with real teeth. It’s not always the brute force of a dictator or a grand system that upends a life. Sometimes it’s just a single stamped document, a missing form, or a box that refuses to fit your story. The smallest bureaucratic decision — a birth certificate, a permit, a ledger entry — can shape someone’s fate just as much as any algorithm or ancient law. What looks like harmless paperwork can bite hard, sometimes quietly, sometimes all at once.

What we need is a civic humility — a willingness to build organizations that, like good scientists, reward self-correction. Harari says the big lesson is to “put aside our fantasies of infallibility, and commit ourselves to the hard and rather mundane work of building institutions with strong self-correcting mechanisms.” It won’t make headlines or fix everything overnight. But it can keep us from repeating the worst mistakes.

Practically, this means keeping humans in the loop. Officials, engineers, and regular citizens need to ask uncomfortable questions about “obvious truths.” Messy debates, audits, and reviews aren’t just noise — they’re how we find errors. In Detroit, reforms now require that facial recognition can’t be the sole reason for an arrest. Governments need independent media and watchdogs. Religious communities can value scholarship and open interpretation, not just literal readings.

Above all, to err is human — and that’s the point. Saint Augustine said, “to persist in error is diabolical.” The institutions that serve us best — science, democracy, open markets — work because they accept human limits and build feedback loops to catch mistakes. Our new tools shouldn’t be an exception. If anything, the complexity of AI demands even more transparency and challenge, not less. An algorithm can’t feel pride or shame when it’s wrong. People can, which is why we need to cultivate a culture that prizes truth over perfection.

As I finish writing, I glance at a folder on my shelf labeled “Mortgage Papers.” Not long ago, a stamped document like that could decide where you lived, who you married, whether you were considered a person or property. Today, a line of code could decide if you get that mortgage, which ads you see, or how you’re ranked for a job. The tools keep evolving — papyrus or pixels, quill or quantum computer — but the underlying story doesn’t change. We build systems to extend our reach, bring order, and make better decisions. They can help. But when we start to worship them, when we stop thinking for ourselves, we’re in trouble. The Bible had a name for idols with an undeserved aura: false gods. In the 21st century, ours might be gleaming databases or hyper-complex models. They promise certainty, and we’re so tired of living with doubt.

But facing uncertainty is the price of wisdom. It separates trust from blind faith. Use the tools, respect the laws, read the scriptures, experiment with AI. But don’t abdicate. Stay curious. Be the error-finder, the conscience in the loop. An algorithm will never have a conscience. That’s our job. If we remember that, we can use what we build without surrendering our humanity. We can keep order and pursue truth, not just settle for the easy comfort of infallibility. In the end, a fallible person who keeps asking questions is safer than any “infallible” system left unchecked. The tiger might be made of paper, silicon, or ideology — but we still need to keep our teeth.

Viz

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Member discussion